This past weekend, Nyanga learners participated in an important workshop on fire awareness and safety. The workshop was conducted by the City of Cape Town’s fire and rescue services, represented by Ms Nombeko Kopele. The learners gathered in their usual tutoring venue at Zolani Centre and learnt interesting and important realities about fire.

The workshop is very relevant to the learners because fire is a real part of many of their lives as some have had their homes destroyed by it. The workshop covered useful practices to engage in when working with fire, including how to handle live flame, such as candles and some lamps; first aid when someone has been subjected to burns and the reporting protocol when there is a fire. The learners got to see pictures of fires in a variety of settings, such as veld and mountain fires, fires in informal settlements and other kinds of buildings, and visually learnt about the kind of devastation fire can cause.

Ms Kopele divided the learners into different groups and the grade 11 and 12 session doubled up as a career guidance workshop, as she spoke to them about fire fighting as a career path that is open to them post Matric. The learners had many questions about the subject choices they should make in order to work in this field and also the benefits of being a fire-fighter. Ms Kopele was up to the task and answered all the questions posed to her. At the end of the workshop were 90 Ikamvanites well informed about fire safety and protocols.

A very special thank you to the City of Cape Town for delivering this important workshop to the Nyanganites.

Hi Ikamvanites!

We are two students from Metropol University College in Copenhagen, Denmark, studying a degree in Global Nutrition and Health. Currently we are based in the beautiful Mother City soaking up the summer sun and doing an internship at IkamvaYouth (IY).

For our internship our idea was to teach a series of cooking classes to a group of 15 students at the Nyanga branch to promote health, educational skills and cultural awareness. To our delight IY liked the idea and said that we could join their team for 3 months. How lucky are we?!

Our aim is to explore ideas around culture and food. Some of the questions we asked ourselves were – What is culture? What constitutes as a ‘meal’ in different cultures? Is it meat and potatoes with some veg on the side or is it an open sandwich with a root vegetable topping or some hering? What utensils do different cultures use to eat a meal with – hands, forks, chopsticks, spoons? How is food presented and how does it stimulate the tastebuds visually? Most importantly – how can we push our own boundaries and develop tastes for new and unfamiliar foods?

The idea is to expose students to unfamiliar ingredients as well as showcase how plant-based foods can be used to prepare a variety of imaginative and tasty dishes. On the one hand we are using ingredients that are not always easily available and on the other hand we want to explore how students can enjoy and introduce fresh and healthy, yet affordable foods into their daily diet.

However, at the heart of any cooking classes should be fun and laughter, and this is exactly what we got up to this weekend for our first proper cooking class.

On the menu was fast-food. We made Danish smørrebrød which is a traditional open sandwich, enjoyed by the Danes at lunchtime. We also got our hands stuck into whipping up and rolling some Japanese inspired veggie sushi.

Between the two countries, Denmark and Japan, Denmark came out on top and the students loved the Danish rye bread and toppings. The sushi however received mixed reviews. Some people were close to vomitting, no jokes 🙂 Oh the DRAMA! It was awesome!

Let’s face it – learning to aquire the taste for the fishy sea vegetable, nori, can take a bit longer than just one afternoon. And then there is the wasabi – the green stuff!! Love it or hate, we had great fun and were all pros at eating with chopsticks by the end of the class.

Check out the pics below! The students simply inspired us with their commitment to the task at hand!

One more thing peeps…

We are planning a Yoga & Lunch Charity Event in the Park and YOU are invited!

We are hoping to raise R5000. All proceeds will go towards the IY cooking classes.

Like us on facebook: Yoga & Lunch Charity Event in the Park and read the ‘ABOUT’ section for more info OR email us at yogaluncheoncharityevent@gmail.com.

AND please show your support and join us for some socialising and feasting on 17 March 2013. The lunch will be prepared by the students. Our first catering event!!

P.S. Any donations are always welcome and would be much appreciated!

Bye for now 🙂

Jepser & Sharline

A mere invitation to the Nyanga Open Day was not enough for New Eisleben High School, who requested that IY come and conduct a second ‘Open Day’ to its leaners in their school hall. The Nyanga team happily obliged and on the 23rd of January, spent precious time with the school’s learners, telling them about IY and the support available for them throughout the year.

The learners listened attentively and asked many questions afterwards, betraying a genuine interest in the program and how it runs. The principal, Mr Mazimela is enthusiastic about the IY model and approach and asked why IY does not launch the tutoring program from the schools, since it is a valuable intervention. This is an exciting query, very much aligned with IY’s 2030 vision, and IY Nyanga is looking forward to working with the school towards 2030, and beyond!

High School students and parents from Nyanga and surrounding areas trekked to Oscar Mpetha High School to hear all about IY Nyanga this last Saturday the 19th of January.

The school hall comfortably seated the 80 people who were in attendance, who included current and prospective Ikamvanites, parents, school staff and volunteers. The branch coordinator, Shuvai Finos welcomed the group, and introduced Funeka’s story, which explains the IY model in 3minutes. Branch Assistant, Asanda Nanise then took over the reins and got straight into fleshing out the IY model as explained by the video clip. Asanda explained the application process, the attendance requirements and the infamous, yet effective kickouts which are conducted every term.

Afterwards, a question and answer segment followed where concerned parents asked whether learners could only attend during Winter School, if they live far from the branch, or alternatively, on Saturdays only. Asanda explained the need for learners to attend regularly so as to get constant and consistent input which is much needed as part of IY’s intervention into learners’ education.

At the end of the session, parents and learners collected application forms and then set off, excited to start the journey towards becoming full-fledged Ikamvanites.

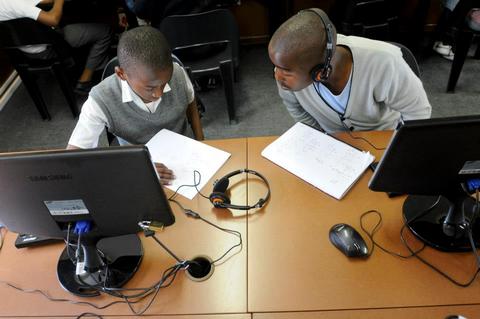

Just over a year ago I was approached by Andrew Einhorn, a UCT grad student, who was interested in implementing an online maths program at Makhaza. All he needed was access to the lab, access to a class and a tutor. A year down the line not only he has completely revamped two of our branches labs in Makhaza and Nyanga, established a formal Khan Academy program in these branches (as well as other locations in Cape Town and rural Eastern Cape), but has produced results at very low costs, and is piloting in schools for 2013.

His passion for creating high impact and stimulating learning environments in township and rural locations often only privy to the wealthy few has seen him start Numeric, an NGO interested in finding ways to bring Khan Academy to South Africa and make it a useful resource to both teachers and learners. He presented an inspiring TEDxUCT talk last year outlining the background, as well as the impact and results Numeric has had. He also posted the following blog on the Khan Academy website:

A little over 15 months ago, we started an experiment. We wanted to know if Khan Academy was viable in township (slum) areas in South Africa and if so, what type of impact it might have on numeracy. Numeracy in South Africa is astonishingly weak, with just 2% of Grade 9s scoring over 50% on the annual national assessments in 2012.

And so we set out to see if Khan Academy might be used as a catalyst for change. But before I expound on the results of this experiment, I ought perhaps give a little more background on the environments we’re working in.

Townships in South Africa are not unlike the favelas of Brazil or the slums bordering Delhi and Calcutta in India. They are urban areas that were, until the end of Apartheid in 1994, reserved for non-whites, but have now become residential hubs for the urbanizing masses. They are typically built on the periphery of cities and tend to be characterized by high population density, poverty and unemployment. Picture a ramshackle of makeshift houses constructed out of corrugated iron, wood scraps and cardboard, jigsawed together into a gigantic maze 5 miles wide and 10 miles across. At the risk of generalising grossly, that’s more or less the picture I want you to have in mind as you read this article.

Now, townships in South Africa get a bad rap. They are viewed as ‘dangerous’ places and it is considered unwise to visit them unless you know someone there, or visit them as part of a ‘township tour’. Yet while crime rates in these areas are often high, the reputation does not do justice to the vibrant and persevering people who inhabit them. In particular, townships are YOUNG! On any given day, around two o’clock in the afternoon, the streets flood with uniformed, backpack-toting children on their way home from school. And despite having barely two pennies to rub together, they are meticulously dressed – shiny black shoes, starched white collars – and have aspirations to match. Most of the children in South Africa live in some form of township, which means that children growing up in these environments constitute the better part of the future of our country.

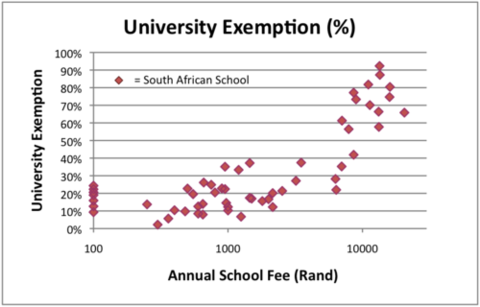

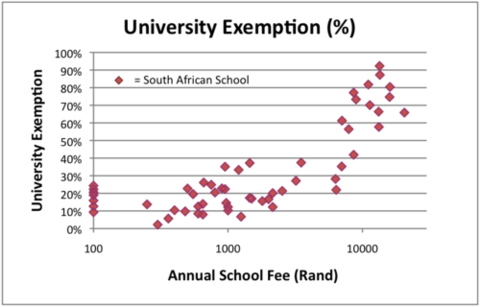

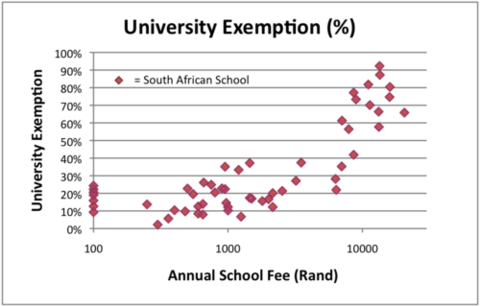

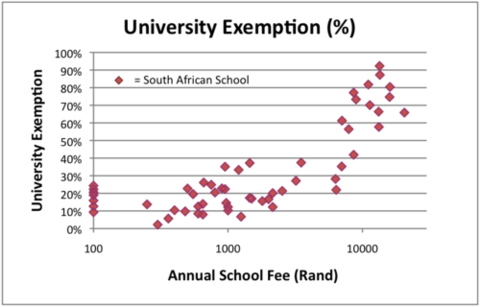

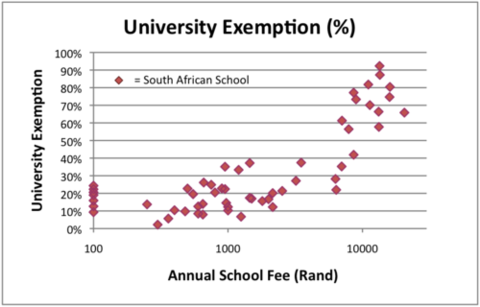

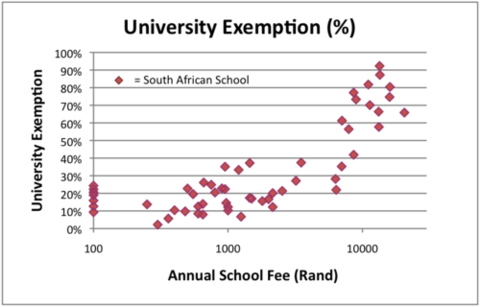

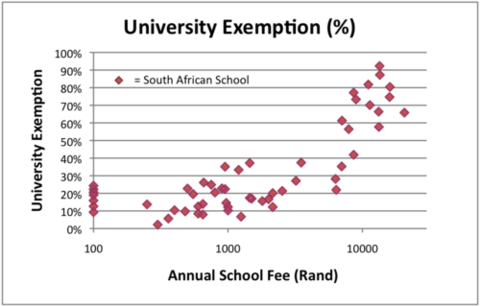

And yet it is supremely difficult to convince our best teachers to go and work in these areas. They are offered good jobs in well-resourced schools most often located in the wealthy suburbs of the cities. Principals at these schools compete fiercely for their skills. And this is as it should be. But it also entrenches the educational bias whereby a child’s access to quality education is directly proportional to the wealth of their family (see chart below).

* University exemption rate refers to the percentage of learners who attain the academic marks in their final year of school that are necessary to gain access to South African universities.

So Numeric’s experiment was to see whether we could use Khan Academy, in conjunction with a slightly less skilled (and often unqualified) math coach, to create the high impact and stimulating learning environments enjoyed by kids living in wealthier suburbs.

The opportunity provided by Khan Academy premised on the following: Videos do not argue about where they are played; they are unaffected by crime and environment. Appropriately licensed, they do not cost anything. They do not grow weary, skip class, or grow jaded. Instead, they convey their message enthusiastically, faithfully, clearly – time and time again. A child may watch just as many videos as he/she has appetite for, and need never feel limited by the dragging on of a boring class or an inept teacher. For many children in South Africa, a Khan Academy video will be their first exposure to what we might term ‘world class instruction’. When complemented by the exercises on the Knowledge Map, Khan Academy becomes a powerful tool for turning the tide on numeracy in South Africa.

So what were the results of the experiment? Well, it’s probably too early to draw any major conclusions, but we do have a few figures we’d like to share. We currently run 7 Khan Academy classes across 3 different hubs in the Eastern and Western Cape provinces of South Africa. The first pilot group of 20 Grade 9s has just completed its first twelve months of Khan Academy and their numbers are as follows:

* Total Khan Academy hours delivered: 2220

* Total Problems Solved: 27,988

* Total Problems per learner: 1399

* Total Khan Modules Complete: 1232

* Average Modules per learner: 62

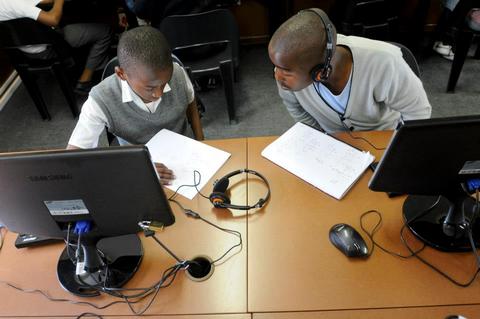

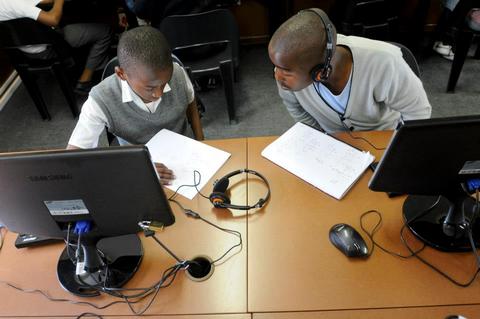

Bearing in mind this is an afterschool programme, these are 27,988 math problems that would not otherwise have been attempted. The 62 modules completed by the average learner constitute 62 gaps that those learners have filled. But it’s more about just the numbers; it’s about creating excitement and enthusiasm around learning. This is hard to convey in words, but perhaps a picture will suffice.

As we always say to our coaches, the tragedy in South Africa is not so much that kids don’t want to learn. It’s that some kids DO want to learn, but can’t. Khan Academy provides us one way to give these kids a world-class education without having to magically replenish our nation’s supply of teachers. And who knows, perhaps one day these kids will become the inspirational and talented teachers we have waited for for so long!

—-

Andrew Einhorn is the founder and current CEO of Numeric.org. His TEDx talk on Numeric.org and Khan Academy is available here.

Just over a year ago I was approached by Andrew Einhorn, a UCT grad student, who was interested in implementing an online maths program at Makhaza. All he needed was access to the lab, access to a class and a tutor. A year down the line not only he has completely revamped two of our branches labs in Makhaza and Nyanga, established a formal Khan Academy program in these branches (as well as other locations in Cape Town and rural Eastern Cape), but has produced results at very low costs, and is piloting in schools for 2013.

His passion for creating high impact and stimulating learning environments in township and rural locations often only privy to the wealthy few has seen him start Numeric, an NGO interested in finding ways to bring Khan Academy to South Africa and make it a useful resource to both teachers and learners. He presented an inspiring TEDxUCT talk last year outlining the background, as well as the impact and results Numeric has had. He also posted the following blog on the Khan Academy website:

A little over 15 months ago, we started an experiment. We wanted to know if Khan Academy was viable in township (slum) areas in South Africa and if so, what type of impact it might have on numeracy. Numeracy in South Africa is astonishingly weak, with just 2% of Grade 9s scoring over 50% on the annual national assessments in 2012.

And so we set out to see if Khan Academy might be used as a catalyst for change. But before I expound on the results of this experiment, I ought perhaps give a little more background on the environments we’re working in.

Townships in South Africa are not unlike the favelas of Brazil or the slums bordering Delhi and Calcutta in India. They are urban areas that were, until the end of Apartheid in 1994, reserved for non-whites, but have now become residential hubs for the urbanizing masses. They are typically built on the periphery of cities and tend to be characterized by high population density, poverty and unemployment. Picture a ramshackle of makeshift houses constructed out of corrugated iron, wood scraps and cardboard, jigsawed together into a gigantic maze 5 miles wide and 10 miles across. At the risk of generalising grossly, that’s more or less the picture I want you to have in mind as you read this article.

Now, townships in South Africa get a bad rap. They are viewed as ‘dangerous’ places and it is considered unwise to visit them unless you know someone there, or visit them as part of a ‘township tour’. Yet while crime rates in these areas are often high, the reputation does not do justice to the vibrant and persevering people who inhabit them. In particular, townships are YOUNG! On any given day, around two o’clock in the afternoon, the streets flood with uniformed, backpack-toting children on their way home from school. And despite having barely two pennies to rub together, they are meticulously dressed – shiny black shoes, starched white collars – and have aspirations to match. Most of the children in South Africa live in some form of township, which means that children growing up in these environments constitute the better part of the future of our country.

And yet it is supremely difficult to convince our best teachers to go and work in these areas. They are offered good jobs in well-resourced schools most often located in the wealthy suburbs of the cities. Principals at these schools compete fiercely for their skills. And this is as it should be. But it also entrenches the educational bias whereby a child’s access to quality education is directly proportional to the wealth of their family (see chart below).

* University exemption rate refers to the percentage of learners who attain the academic marks in their final year of school that are necessary to gain access to South African universities.

So Numeric’s experiment was to see whether we could use Khan Academy, in conjunction with a slightly less skilled (and often unqualified) math coach, to create the high impact and stimulating learning environments enjoyed by kids living in wealthier suburbs.

The opportunity provided by Khan Academy premised on the following: Videos do not argue about where they are played; they are unaffected by crime and environment. Appropriately licensed, they do not cost anything. They do not grow weary, skip class, or grow jaded. Instead, they convey their message enthusiastically, faithfully, clearly – time and time again. A child may watch just as many videos as he/she has appetite for, and need never feel limited by the dragging on of a boring class or an inept teacher. For many children in South Africa, a Khan Academy video will be their first exposure to what we might term ‘world class instruction’. When complemented by the exercises on the Knowledge Map, Khan Academy becomes a powerful tool for turning the tide on numeracy in South Africa.

So what were the results of the experiment? Well, it’s probably too early to draw any major conclusions, but we do have a few figures we’d like to share. We currently run 7 Khan Academy classes across 3 different hubs in the Eastern and Western Cape provinces of South Africa. The first pilot group of 20 Grade 9s has just completed its first twelve months of Khan Academy and their numbers are as follows:

* Total Khan Academy hours delivered: 2220

* Total Problems Solved: 27,988

* Total Problems per learner: 1399

* Total Khan Modules Complete: 1232

* Average Modules per learner: 62

Bearing in mind this is an afterschool programme, these are 27,988 math problems that would not otherwise have been attempted. The 62 modules completed by the average learner constitute 62 gaps that those learners have filled. But it’s more about just the numbers; it’s about creating excitement and enthusiasm around learning. This is hard to convey in words, but perhaps a picture will suffice.

As we always say to our coaches, the tragedy in South Africa is not so much that kids don’t want to learn. It’s that some kids DO want to learn, but can’t. Khan Academy provides us one way to give these kids a world-class education without having to magically replenish our nation’s supply of teachers. And who knows, perhaps one day these kids will become the inspirational and talented teachers we have waited for for so long!

—-

Andrew Einhorn is the founder and current CEO of Numeric.org. His TEDx talk on Numeric.org and Khan Academy is available here.

Lloyd Lungu

Lloyd Lungu